Do IVF Babies Have Fertility Problems?

When you hear about in vitro fertilization (IVF), it’s often tied to stories of hope—couples overcoming infertility to welcome a baby into their lives. Over 10 million babies have been born through IVF worldwide since the first “test-tube baby,” Louise Brown, arrived in 1978. It’s a remarkable achievement. But as these babies grow up, a question lingers in the minds of parents, doctors, and even the kids themselves: Will IVF babies face fertility problems of their own when they’re ready to start families?

It’s a fair worry. If your parents needed help to conceive you, does that mean you’ll need help too? The good news is that science is starting to give us answers, and they’re more reassuring than you might expect. In this deep dive, we’ll explore what we know about the fertility of IVF babies, unpack the latest research, and address the concerns that don’t always make it into the headlines. Whether you’re a parent considering IVF, an IVF baby yourself, or just curious, stick around—there’s a lot to unpack here.

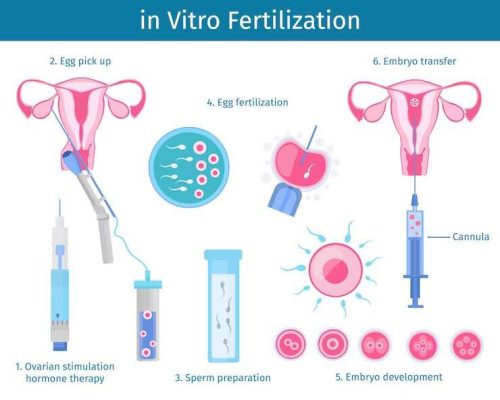

The Basics: What Happens in IVF?

IVF is like a high-tech assist for nature. Doctors take an egg from a woman’s ovaries, mix it with sperm in a lab, and let an embryo grow for a few days. Then, they place it back into the womb, hoping it sticks and becomes a baby. Sometimes, it’s a straightforward process; other times, it involves extra steps like using donor eggs or sperm, or injecting sperm directly into the egg (a method called ICSI).

The process is amazing, but it’s not exactly how babies are made in the wild. That difference has sparked curiosity about whether it affects the kids born this way—especially when it comes to their own ability to have children later in life. Could the lab environment, the medications, or even the reasons their parents needed IVF in the first place leave a mark?

Are IVF Babies Different From Naturally Conceived Kids?

Let’s start with what we see at birth. IVF babies sometimes face a bumpier start—higher chances of being born early, having a low birth weight, or even having certain birth defects like heart or muscle issues. Studies show the risk of congenital malformations is about one-third higher in IVF kids compared to those conceived naturally. For example, cardiac malformations have an odds ratio of 1.29, meaning they’re 29% more likely in IVF babies.

But here’s the catch: these differences don’t necessarily mean IVF itself is the culprit. Often, it’s the infertility that led to IVF in the first place—like blocked tubes or low sperm count—that might play a role. Plus, IVF pregnancies are more likely to involve twins or triplets, which naturally ups the odds of complications. So, while IVF babies might start life with a few extra hurdles, do these early challenges hint at fertility struggles down the road? Not necessarily. Let’s dig deeper.

The Big Question: Can IVF Babies Have Kids of Their Own?

Here’s where things get exciting—and a little complicated. Since IVF has only been around for about 45 years, the oldest IVF babies are just hitting their 40s. That means we’re only now starting to see how they fare when they try to start their own families. The data is still growing, but what we have so far is pretty encouraging.

A groundbreaking study from 2022 followed young adults born through IVF in Melbourne, Australia. These folks, now in their 20s and 30s, showed no major red flags when it came to their reproductive health. Their hormone levels—like testosterone and estrogen—were in normal ranges, and their quality of life matched that of people conceived naturally. Another study from the Netherlands tracked over 24,000 IVF kids into their 20s and found no increased risk of infertility compared to kids from subfertile parents who didn’t use IVF.

So, the short answer? IVF babies don’t seem to have a built-in fertility disadvantage just because of how they were conceived. But there’s more to the story, and it’s worth exploring the details.

What About the Boys?

For boys born through IVF, one worry is whether their sperm will be up to the task later on. If their dads needed ICSI because of low sperm count or poor sperm quality, could that trait pass down? Early research says it’s not a simple yes or no.

A small study from Belgium looked at 54 young men conceived via ICSI in the 1990s. Their sperm counts were lower than average—about half of what naturally conceived men had. But here’s the twist: their dads had severe sperm issues, so this might be more about genetics than the ICSI process itself. Other studies, like one from Denmark, found that IVF boys had normal puberty timing and hormone levels, suggesting their reproductive systems develop just fine.

And the Girls?

For girls, the focus is often on their ovaries and eggs. Could the medications their moms took to boost egg production—or the lab environment where they started as embryos—affect their future fertility? So far, the evidence says no. A 2023 review of girls born through IVF found their menstrual cycles, hormone levels, and ovarian reserves (the number of eggs they have left) were similar to those of their naturally conceived peers.

One cool finding? Some researchers checked the ovarian health of IVF girls using ultrasound and blood tests. Their “egg bank” looked just as robust as anyone else’s. That’s a big relief for parents who might wonder if they’ve passed on a ticking clock.

The Genetic Factor: Is It Nature or Nurture?

Here’s where it gets tricky. If your parents needed IVF because of a genetic condition—like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or a sperm-related gene mutation—there’s a chance you could inherit that issue. For example, if Dad has a Y-chromosome glitch that tanks his sperm count, his IVF son might face the same hurdle. Same goes for Mom’s PCOS potentially showing up in her daughter.

But this isn’t unique to IVF. Naturally conceived kids inherit traits too. The difference with IVF is that it sometimes lets people with severe infertility have kids when they couldn’t otherwise. So, the question isn’t really “Does IVF cause fertility problems?”—it’s “Does the infertility that led to IVF get passed on?” In many cases, it might, but IVF itself doesn’t seem to add an extra layer of trouble.

Epigenetics: A Hidden Twist?

There’s a buzzword in science called epigenetics—changes in how genes work without altering the DNA itself. Some worry that the IVF process (think lab dishes and freezing embryos) might tweak these settings in ways that affect fertility later. Studies in mice show that IVF can mess with gene “switches” tied to growth and health, but in humans, the picture is fuzzier.

A 2022 paper found that IVF kids have slightly higher rates of imprinting disorders—rare conditions where gene expression goes haywire. Could this impact fertility? Maybe, but the risk is tiny (we’re talking less than 1%), and there’s no solid link to infertility yet. Scientists are still watching this space, and it’s one of those areas where we need more grown-up IVF babies to weigh in.

Real Stories: What IVF Adults Are Saying

Numbers are great, but what about the people living this? Meet Sarah, a 32-year-old from California who was born via IVF in 1992. “My mom always worried I’d struggle to have kids because she did,” Sarah says. “But I got pregnant naturally last year—no issues at all.” Her story isn’t rare. Online forums like Reddit and X are full of IVF adults sharing similar experiences, with many saying their fertility feels “normal” so far.

Then there’s James, a 28-year-old from London conceived through ICSI. He got tested last year out of curiosity and found his sperm count was on the lower side. “My dad’s was awful, so maybe it’s from him,” he shrugs. “But my doctor says I can still have kids with a little help if I need it.” These real-life snapshots hint that while genetics might play a role, IVF itself isn’t the dealbreaker.

Interactive Quiz: How Much Do You Know About IVF Babies?

Let’s take a quick break and test your knowledge! Answer these questions and see how you stack up:

- True or False: IVF babies are always born with health problems.

- A) True

- B) False

- What’s one reason IVF babies might have fertility issues?

- A) The lab equipment

- B) Inherited traits from parents

- C) The doctor’s skills

- How old is the oldest IVF baby today?

- A) 25

- B) 45

- C) 65

(Answers: 1-B, 2-B, 3-B. How’d you do? Share your score in the comments!)

Busting Myths: What People Get Wrong

There’s a lot of chatter out there about IVF babies, and not all of it holds up. Let’s clear the air:

- Myth #1: IVF babies are infertile because they’re “artificial.” Nope. The process mimics natural conception—just in a lab. Studies show their reproductive systems work like anyone else’s.

- Myth #2: All IVF kids need IVF to have kids. Not true. Many conceive naturally, especially if their parents’ infertility wasn’t genetic.

- Myth #3: IVF messes up your DNA. While epigenetics is a question mark, your core DNA stays intact. IVF doesn’t “rewrite” who you are.

The Science Gaps: What We Don’t Know Yet

Even with all this research, there are still blind spots. Most studies focus on IVF kids in their teens or 20s—not enough have hit their 30s or 40s, when fertility really gets tested. Plus, IVF keeps evolving. Today’s frozen embryos and single-embryo transfers weren’t the norm 20 years ago, so older data might not match modern outcomes.

Another gap? Long-term tracking. Imagine a global registry of IVF adults sharing their health stats as they age—that’d be gold for science. Right now, we’re piecing together small studies, which leaves room for surprises. For instance, could subtle epigenetic shifts show up in the next generation (IVF grandkids)? It’s a wild thought, and one researchers are starting to explore.

Practical Tips for IVF Parents and Kids

Worried about the future? Here’s how to stay ahead of the game:

For Parents Considering IVF

- ✔️ Ask about your infertility cause. If it’s genetic, talk to a counselor about what might pass down.

- ✔️ Opt for single-embryo transfer. It cuts risks like prematurity that could affect long-term health.

- ❌ Don’t stress over the process itself. The evidence says IVF doesn’t “curse” your kid’s fertility.

For IVF Adults

- ✔️ Get a checkup. A simple hormone test or semen analysis can give you peace of mind.

- ✔️ Live healthy. Diet, exercise, and avoiding smoking boost fertility for everyone—IVF or not.

- ❌ Don’t assume you’re doomed. Your odds are likely as good as anyone else’s unless genetics say otherwise.

Step-by-Step: Checking Your Fertility

- Visit a doctor. Tell them you’re an IVF baby—they’ll know what to look for.

- Test the basics. Women can check ovarian reserve; men can do a sperm count.

- Review family history. If your parents had a specific issue, ask if it’s hereditary.

- Plan ahead. If you spot a problem, options like egg freezing or IVF are there for you too.

A Fresh Angle: The Mental Health Connection

Here’s something you won’t find in most articles: how growing up as an IVF baby might affect your mindset about fertility. A 2022 study from the Raine Cohort in Australia found that IVF teens had a slightly higher rate of depression at age 14 (12.6% vs. 8.5% for naturally conceived kids). But by 17, the gap closed. Interestingly, kids of subfertile parents (who didn’t use IVF) also showed higher depression rates, hinting it’s more about family stress than the IVF process.

Why does this matter? If you’re an IVF kid, the pressure to “prove” your fertility—or anxiety about repeating your parents’ struggles—could weigh on you. Talking to a counselor or joining a support group might ease that load. It’s a piece of the puzzle that’s often overlooked but could shape how you approach family planning.

Poll: What’s Your Take?

Time for you to weigh in! Pick one and vote in the comments:

- A) I think IVF babies have the same fertility odds as anyone else.

- B) I’m worried IVF might cause problems we don’t see yet.

- C) It depends on the parents’ infertility, not IVF itself.

The Future: What’s Next for IVF Babies?

As more IVF kids grow up, we’re entering uncharted territory. Picture this: in 10 years, we’ll have a wave of IVF adults in their 50s. Will their fertility stories match their naturally conceived peers? Early signs say yes, but science loves a curveball. Researchers are already planning studies on IVF grandkids—yep, the babies of IVF babies—to see if anything unexpected pops up.

One wild card? Advances like in vitro gametogenesis (IVG), where scientists might one day make eggs or sperm from skin cells. If IVF kids ever need a boost, that could be a game-changer. For now, it’s sci-fi territory, but it’s a glimpse of how far this field might go.

A Simple Calculation: What Are the Odds?

Let’s crunch some numbers for fun. Say 1 in 6 couples face infertility (per the World Health Organization). If IVF babies inherit that same baseline risk—and no extra from the process—about 16% might need help conceiving. Compare that to the Belgian ICSI study, where 50% of guys had lower sperm counts but could still father kids with help. The real risk seems tied to family history, not IVF itself. It’s not rocket science, just a reminder that genetics often call the shots.

Wrapping It Up: Hope Over Hype

So, do IVF babies have fertility problems? Based on what we know today, the answer leans toward “no”—at least not because of IVF itself. Their reproductive health looks solid, with any hiccups more likely tied to the infertility their parents faced. Science is still catching up, but the vibe is optimistic. IVF kids are growing up, having kids, and living their lives, often without a hitch.

For parents, this is a sigh of relief. For IVF adults, it’s a green light to plan your future without extra baggage. And for the curious, it’s a peek into how science and nature dance together. Got thoughts or stories of your own? Drop them below—let’s keep this conversation going!